Duty to Care

Duty to Care

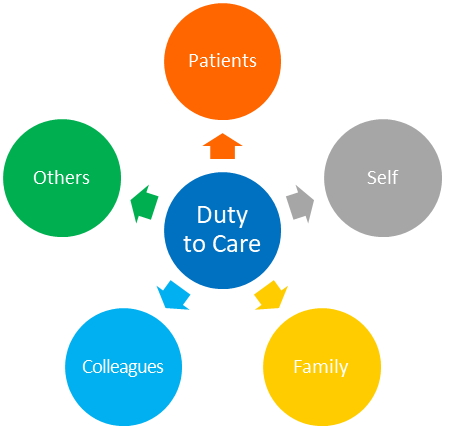

For the purpose of this document, “duty to care” is viewed from primarily an ethical, rather than a legal perspective. The Ontario Health Plan for an Influenza Pandemic states that a healthcare worker has “an ethical duty to provide care and respond to suffering. (OHPIP, 2008) The University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics 2005 paper Stand on Guard for Thee reiterates the ethical duty to care that healthcare professionals owe the public. (Joint Centre for Bioethics, 2005)

Both documents do acknowledge that the duty to care is contextual and many factors can affect a practitioner’s ability to provide optimal patient/client care.

During a pandemic outbreak, several private day care centers close. An RT who works in the emergency department at a large teaching hospital is the single parent of a child who attends one of these day care facilities. The hospital is experiencing a significant increase in visits to the emergency department and several of the hospital’s staff RTs are already off sick. What is the best course of action for this particular RT?

The ethical principles are to act fairly, do good and do no harm.

In this circumstance, the RT is required to balance the needs of the RT’s patients/clients with the needs of their child. It is not clear that patient/client care would suffer if they did not come into work (e.g., there is other staff who can provide the same care). However, if they were unable to make other babysitting arrangements, the RT would not legally or morally be able to leave their child unattended. Members are encouraged to anticipate and seek to address factors that may interfere with their ability to carry out their professional duties.

During a severe respiratory outbreak, an RT is unwilling to come to work due to their concern that they will contract the illness and bring it home to their elderly father. Can they refuse to work under the Occupational Health and Safety Act?

The ethical principles are to act fairly, do good and do no harm

Respiratory Therapists care for patients with respiratory illnesses every day, and this is inherent in the work that they do. Additionally, an RT’s refusal to provide their services could potentially endanger the life, health, or safety of these patients. Therefore, in this circumstance, the RT is expected to fulfill the requirements of their job.

At times, multiple obligations can result in conflicting priorities which are quite specific to each individual. Therefore, each RT must ultimately balance their own reality with the best interest of their patient/client. When faced with managing conflicting duties, the expectation of the College is that its Members will, to the very best of their abilities, provide ethical, safe, and competent patient/client care.

S.43(1) of the Occupational Health & Safety Act (1990) delineates under what circumstance certain types of employees can refuse work due to fear of exposure to a hazard. This act clearly articulates that hospital workers do not have a right of refusal to work if:

- if the hazard is inherent in the work the employee does; or

- when the employee’s refusal to work would directly endanger the life, health, or safety of another person.¹

FOOTNOTES

1. Occupational Health & Safety Act. (1990). Legislative Assembly of Ontario.